I can’t keep up with Dr. Oz. Just when I thought the latest weight loss miracle was raspberry ketone, along comes another weight loss panacea. This time, it’s green coffee beans.

Eveyone knows Dr. Oz, now. Formerly a guest on Oprah, he’s got his own show which he’s built into what’s probably the biggest platform for health pseudoscience and medical quackery on daytime television. In addition to promoting homeopathy, he’s hosted supplement marketer Joe Mercola several times to promote unproven supplements. He has been called out before for promoting ridiculous diet plans, and giving bad advice to diabetics. And don’t forget his failed attempt to actually demonstrate some science on his show, when he tested apple juice for arsenic which prompted a letter from the FDAabout his methodology. His extensive track record of terrible health advice is your caution not to accept anything he suggests at face value. So when the sign in front of my local pharmacy started advertising “Green coffee beans – as seen on Dr. Oz”, I tracked down the clip in question. The last time I saw Dr. Oz in action when when he had SBM’s own Steven Novellaas a guest, where there was actually a exchange (albeit brief) about the scientific evidence for alternative medicine. Replace Dr. Novella with a naturopath, and you get this:

Yes, Oz did use the terms “magic”, “staggering”, “unprecedented”, “cure” and “miracle pill”. And clearly the naturopath, Lindsay Duncan, is enamored with this product. But Dr. Oz is a health professional – he’s the Vice-Chair of the Department of Surgery at Columbia University. He’d be a bit skeptical, right? This exchange at the end, made me shake my head – Dr. Oz really has crossed the woobicon:

Now I always pride myself at having the smartest TV audience out there. So I’m hoping that some of you are skeptical about this. I was certainly skeptical about it. Am I speaking for a couple of you, anyway? It does seem a little too good to be true.

So what did Dr. Oz do – issue cautions about obesity panaceas? No. He created some anecdotes:

So I gave the supplements to two viewers 5 days ago. I gave all the information I could find on this product to our medical unit, they did diligent work, but we still wanted to see what would happen in real life.

One viewer dropped 2 pounds in 5 days. The other viewer lost 6 pounds in 5 days. Convincing weight loss? It was persuasive to Dr. Oz.

So now I’m going to do what Dr. Oz, the producers of the show, and the naturopath Lindsay Duncan didn’t do — actually review the evidence.

The Evidence Check

There is some suggestion, but no convincing evidence, that coffee consumption or caffeine consumption may have a modest, effect on weight. This study examined unroasted or “green” coffee beans, and was published in the online journal Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity: Targets and Therapy. The journal says it’s a peer-reviewed publication, but with an average of 12 days from submission to editorial decision, which apparently includes peer review, it’s obvious the review is cursory at best. The study is entitled Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, linear dose, crossover study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of a green coffee bean extract in overweight subjects. The lead author, Joe A Vinson, is a chemist at the University of Scranton, Pennsylvania. None of the three authors appear to be clinicians or medical professionals, and none appear to have published obesity-related research before, according to PubMed. The study was funded by a supplement manufacturer, Applied Food Sciences.

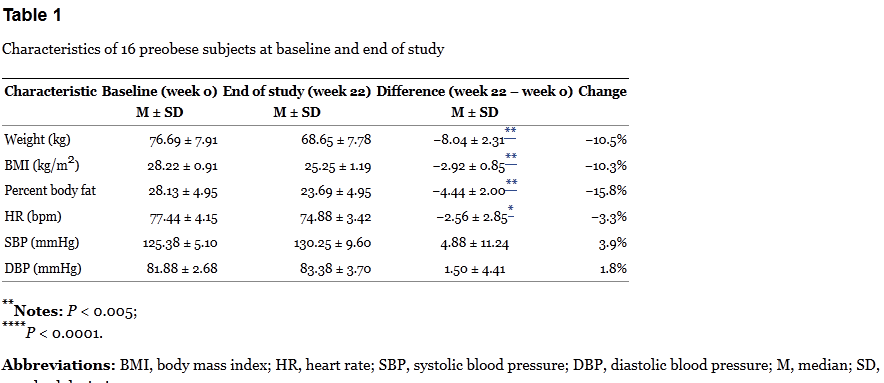

To start — this is a very tiny trial — just 16 patients (8 males, 8 females) with an average age of 33 years. The research location was a hospital in Bangalore, India. How these patients were recruited was not disclosed. Normally a trial would list detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria, and then describe how many patients were considered and the reasons for exclusion. This paper just reports the final number, and there is no information provided on why 16 was felt to be the desireable number. The average weight was 76.6kg (168 lbs) and the average body mass index (BMI) was 28.22. While the BMI on an individual basis may not be informative, when looking at a population, a score between 25 and 30 is usually accepted to mean overweight, but not obese. The details on how these measurements were taken were not well described — which is surprising, given this is a this is a pretty important part of the study.

One of the tricks that researchers (both pharma and supplement) can play when conducting clinical trials is to change parameters of the trial, after the trial is started. Because of the risk of conflicts of interest, there has been a growing commitment to publish the trial parameters in advance of the trial at the website clinicaltrials.gov. Many medical journals will now refuse to publish a trial if it was not initially entered into a public registry. Not only does a registry ensure that negative results don’t disappear, it gives valuable information about the study, including its design, entry criteria, and who gave formal ethics approval for the study. This study was never registered at clinicaltrials.gov. And there’s no evidence provided that a research ethics board ever reviewed the protocol. I find it hard to believe that any investigator would undertake a clinical trial of an unproven supplement without obtaining prior ethics approval – but that seems to be the case.

Green coffee extract (the brand “GCA”) was used in the study. The authors note that GCA has a standardized content of 45.9% chlorogenic acid, which is purported to be the active ingredient. Now contrary to what was said on the Dr. Oz show, chlorogenic acid is also in roasted coffee in significant amounts, so you don’t need to take green coffee extractto get a good dose. Patients were “randomly” divided (method was not disclosed) into three groups: high dose, low dose, and placebo (which was described only as an “inactive substance”). No clear justification for how the dose was determined was provided. Each group stayed in one group for six weeks, had a washout of two weeks, then moved to the next group. Here’s where we run into more problems.

Double-blind in name only

Groups served as their own controls, and rotated betwen a “high dose”, a “low dose” and the placebo.

- Group 1 (6 patients): High dose (x 6 weeks) — washout (x 2 weeks) — low dose (x 6 weeks)- washout (x 2 weeks) — placebo (x 6 weeks)

- Group 2 (4 patients): Low dose — washout — placebo — washout — high dose

- Group 3 (6 patients): Placebo — washout — high dose — washout — low dose

This doesn’t look that unreasonable. But the investigators noted the following:

The high-dose condition was 350 mg of GCA taken orally three times daily. The low-dose condition was 350 mg of GCA taken orally twice daily. The placebo condition consisted of a 350 mg inert capsule of an inactive substance taken orally three times daily.

Wait, what? The low dose arm was twice daily, while the placebo and the high dose arm were three times per day? That means that participants and investigators could determine which period was the “low dose” treatment. Knowing this, the other two treatment periods can be determined. So much for blinding and placebo control – we can’t credibly consider this to a blinded trial.

Based on the protocol, participants were evaluated at weeks 0, 6, 8, 14, 16, and 22. Diet was assessed by interviews and recall — a notoriously unreliable means of measuring actual calorie consumption. Weight, height, body fat, and blood pressure were calculated each visit. So here are the results for the three groups:

The table above is where Dr. Oz got his statistics of “17 lbs” of weight loss and 10% weight loss over 22 weeks. Oz also points out that there is no reported difference in dietary intake at the beginning and end of the trial – which is correct, but this is based only on patient recall. So is the weight loss due to the intervention? The group-by-group results are baffling.

Spot anything odd? Check out the HD/LD/PL group. This group lost about 4kg during the 6-week treatment period, but then lost an additional 4kg during the washout. There was relatively no change thereafter on the low dose. The PL/HD/LD group is even odder. In the first eight weeks of no active treatment (placebo & washout), the group lost about 8kg, but then didn’t budge on the high dose, and lost about 1kg on the low dose. Finally the LD/PL/HD group lost about 3kg on the low dose, was flat on the placebo, and then lost a smaller amount of weight on the high dose, which continued during the washout.

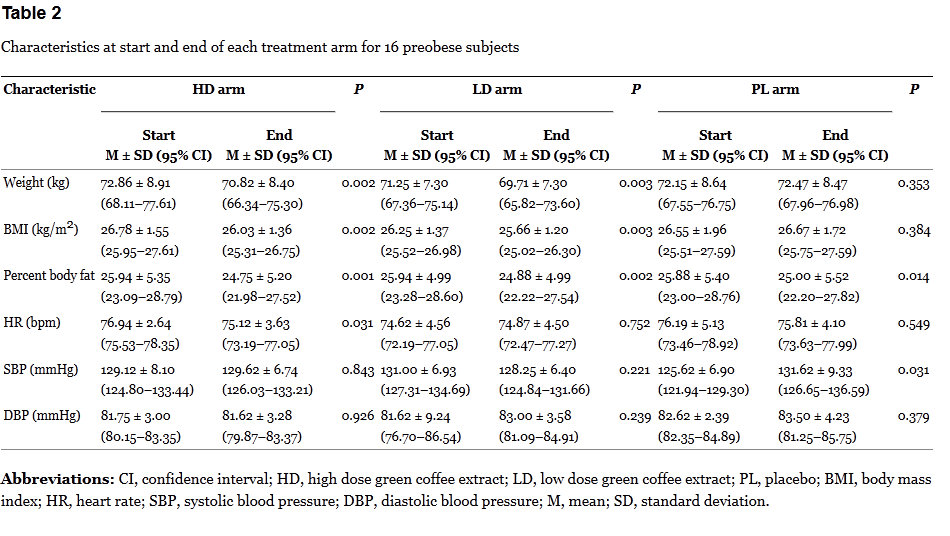

The results don’t add up. If the green coffee is having an actual effect, it should be occuring when the dose is given, not during the washout, or when a placebo is taken. Bias? Random noise? In a tiny, poorly-controlled trial, it’s not possible to say. The breakdown of the results by arm are interesting:

Here it’s a bit more revealing. The changes in each period are modest. Given the small sample size, the repeated measurements, and lack of proper blinding, the risk of bias is high.

Safe and Effective?

Both Oz and the authors state that the supplement was safe and free of side effects. But the trial doesn’t report any side effect information at all, other than stating “no side effects of using GCA”. Given no information seems to have been systematically collected, it’s not clear we can accept this statement. At a minimum, the authors should have reported side effects between the three treatment periods. Surprisingly, there was a non-significant increase in systolic and diastolic blood pressure, which the authors note appeared restricted to the placebo treatment component.

Did the weight loss last? The authors claim that 14 of 16 participants maintained their lowered weight after completing the study – this is doubtful, as no supplement or medication for obesity continues to work after you stop taking it.

The Red Flag Bogus Weight Loss Test

Diet products that promise rapid weigh loss with no exercise or calorie restriction are nothing new. The Federal Trade Commission routinely takes on on diet supplement scams, and has a list of claims it calls “red flags” in advertisements for worthless products. Let’s put green coffee beans to that test:

- Cause weight loss of two pounds or more a week for a month or more without dieting or exercise? Weight loss claim is just under 1lb/week with no dieting or exercise.

- Cause substantial weight loss no matter what or how much the consumer eats?Investigators claim there was no difference in calorie type or intake, yet weight loss occurred.

- Cause permanent weight loss (even when the consumer stops using product)?Investigators claimed weight loss sustained after trial ended.

- Block the absorption of fat or calories to enable consumers to lose substantial weight? Actual mechanism (if any) is not clear. On the show it’s called a “fat blocker”.

- Safely enable consumers to lose more than three pounds per week for more than four weeks? Claims 10% over 22 weeks.

- Cause substantial weight loss for all users? Study claims all participants lost weight, lost fat, and reduced their BMI.

- Cause substantial weight loss by wearing it on the body or rubbing it into the skin? — not applicable

The Dr. Oz segment raises several of the FTC’s red flags – if it was a paid commercial message, you could report it to the FTC.

Conclusion

Green coffee bean supplements have the characteristics of a bogus weight loss product. The supplement lacks plausibility, the only published clinical trial is tiny, and it appears to have have some serious methodological problems. Ignoring all of this, Dr. Oz has instead embraced it as the newest panacea for weight loss. Obesity is a real health issue, yet Dr. Oz seems quite content touting unproven products instead of providing credible, science-based information. In the real world, permanent weight loss is difficult, and there are no quick fixes. But not in the Land of Oz.

Reference

Vinson, Joe A, Burnham, Bryan R, & Nagendran, Mysore V (2012). Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, linear dose, crossover study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of a green coffee bean extract in overweight subjects Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity: Targets and Therapy (5), 21-27 DOI: 10.2147/DMSO.S27665

Source : http://www.sciencebasedmedicine.org/dr-oz-and-green-coffee-beans-more-weight-loss-pseudoscience/